Corrections House

Scott Kelly - wywiad

Click here for the English version of this article

Corrections House skupia w jednym miejscu takich muzyków jak Mike IX Williams (Eyehategod), Scott Kelly (Neurosis), Bruce Lamont (Yakuza), Sanford Parker (Minsk). Genialne połączenie elementów industrialu, noise’u, metalu urozmaiconych akustyczną gitarą oraz saksofonem. Po singlu, który ukazał się na początku 2013 roku, w październiku zespół wydał pierwszy album Last City Zero i odwiedził Polskę na pierwszej europejskiej trasie po jego premierze. Przed wrocławskim koncertem wywiadu udzielił nam Scott Kelly.

Na pierwsze koncerty, jakie w zeszłym roku zagraliście pod szyldem Corrections House, składały się solowe występy akustyczne i finał, w którym graliście razem. Następnie tej wiosny wydaliście siedmiocalówkę z dwoma utworami, którym towarzyszyły teledyski, a na jesieni album o bardzo oryginalnym brzmieniu. W jaki sposób Corrections House właściwie stało się zespołem o tak szczególnym pomyśle na kompozycje i brzmienie, jakie możemy usłyszeć na albumie?

To był bardzo naturalny proces. Graliśmy razem koncerty i w pewnym momencie zaczęliśmy tworzyć pewien materiał z myślą o umieszczeniu go w setliście. Te kawałki miały określić niektóre fragmenty, które częściej graliśmy. A potem po prostu weszliśmy do studia i zaczęliśmy nagrywać. Już mniej więcej w połowie trasy udaliśmy się do studia i nagraliśmy sporo materiału.

Wszyscy gracie w różnych grupach o bardzo wyrazistym brzmieniu. Czy w tym projekcie staraliście się celowo osiągnąć brzmienie, które będzie wyraźnie odbiegać od innych zespołów, w których gracie?

Nie, to była naturalna kolej rzeczy, która wynikała z decyzji o wspólnym graniu. To wszystko. Nie chcieliśmy nawet zakładać zespołu. Temat po raz pierwszy pojawił się w naszych rozmowach rok temu i to tylko dlatego, że planowaliśmy trasę, w której Bruce, Mike i ja mieliśmy prezentować nasze solowe dokonania. To się po prostu wydarzyło, kiedy zaczęliśmy planować wspólny występ na końcu koncertu, a potem przyłączył się Stanford i ani się obejrzeliśmy, jak mieliśmy zespół. Nie mieliśmy żadnej wcześniej opracowanej koncepcji – nasze brzmienie wzięło się z tego, jak chcieliśmy brzmieć na koncertach.

W jakim stopniu decyzja o założeniu tego projektu wynikała z kwestii muzycznych, a w jakim stopniu była związana z filozoficznym pokrewieństwem i wspólnymi poglądami na temat świata?

To, że mamy podobne poglądy, to przypadek – nasz projekt jest stricte muzyczny. Ciągnie nas do siebie i do jednej sceny po części dlatego, że mamy podobne poglądy na muzykę i świat.

Czy możesz coś powiedzieć o książce „Cancer as a Social Activity” („Rak jako czynność społeczna”) Mike’a IX Williamsa, która jest punktem odniesienia dla waszych tekstów? Nie sądzę, żeby wiele osób w Polsce ją znało.

Nie mogę zbyt wiele powiedzieć na ten temat, bo to książka Mike’a, to Mike jest jej autorem i wydawcą. Mike, kiedy wydałeś swoją książkę?

Mike: W 2003 roku.

To zbiór esejów i wierszy, refleksji. To świetna książka, można ją od niego bezpośrednio zamówić.

Chyba widziałem ją nawet na Amazonie.

Ale za masę kasy.

Czy korzystaliście z wierszy z tej książki na zasadzie 1:1 czy przeredagowaliście je, żeby pasowały do piosenek? A może chodziło raczej o samo odniesienie do tematyki tej książki?

Po prostu wykorzystywaliśmy je tam, gdzie pasowały.

Mike: W studio napisaliśmy też nowe teksty.

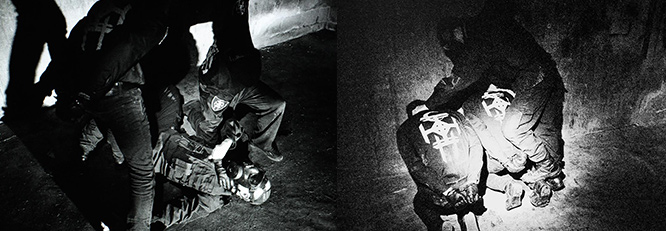

Strona wizualna projektu jest bardzo mocna, czasem nawet dość niepokojąca. Ile wysiłku samodzielnie w to wkładacie?

Autorem naszych teledysków jest Brian Sowell. Przedstawił nam wstępne wersje paru rzeczy, ale my też podsunęliśmy mu kilka pomysłów, więc w tym sensie jest to współpraca – choć to on jest wykonawcą, a my tylko dajemy sugestie. Inne wizualne elementy zespołu – symbol, flagi, zdjęcia i tak dalej, to już wyłącznie nasz pomysł.

W Waszych teledyskach i na zdjęciach promocyjnych czuć opresyjną atmosferę państwa policyjnego, niektóre kojarzą mi się nawet ze zdjęciami z Guantanamo albo wojskowych więzień w Iraku. Czy to jest coś, do czego chcieliście się odnieść?

Oczywiście, to jest nasza aktualna rzeczywistość. To był nasz zamysł, to właśnie chcemy przekazać za pomocą elementów wizualnych, image'u grupy, zdjęć i ogólnego klaustrofobicznego i paranoicznego brzmienia naszej muzyki. To refleksja na temat rzeczywistości, w której wszyscy żyjemy, w której wszyscy jesteśmy obserwowani i znajdujemy się pod ścisłą kontrolą – takie działanie wydawało nam się konieczne.

Do tego na koncertach wszyscy macie mundury, a Seward Fairbury to Wasz „minister propagandy”, przez co otoczka zespołu nabiera militarnego charakteru. W przeszłości grupy, które uciekały się do takich odniesień bywały oskarżane o prawicowe sympatie i tym podobne sprawy. Ludzie i media często tego nie rozumieli. Przydarzyło się to nawet The Clash – niektórzy byli oburzeni utworem „White Riot”, który w rzeczywistości miał wydźwięk antyrasistowski, ale niektórzy skupiali się tylko na tytule i traktowali go dosłownie. Czy coś podobnego przydarzyło się także i Wam?

Nic takiego, o ile wiem, jeszcze nie miało miejsca. Jeśli takie coś może zainspirować ludzi do dyskusji, to chyba coś dobrego, ale mam nadzieję, że ludzie, które znają naszą historię, wiedzą, kim jesteśmy i po jakiej stoimy stronie zrozumieją, że chodzi o karykaturę munduru, że nie mamy zamiaru założyć partii politycznej ani nic z tych rzeczy. Chcemy wnieść jakiś wkład w nasze otoczenie i mam nadzieję, że na naszych koncertach słuchacze zdają sobie z tego sprawę na jakimś poziomie.

Debata na temat tego, czy sztuka powinna być związana z polityką, czy ma potencjał do wywołania społecznych lub politycznych przemian toczy się od wieków, ale zachodnia muzyka wydaje się wycofywać z tego punktu widzenia. W ciągu XX wieku na całym świecie było wielu społecznie i politycznie zaangażowanych wokalistów, również wiele zespołów punkowych i hardcore’owych miało polityczny przekaz. Teraz mamy ruch Occupy, odczuwamy konsekwencje kryzysu finansowego, w wielu krajach mają miejsce niepokoje społeczne, ale gdyby przyjrzeć się temu, ile politycznych tematów poruszanych jest w zachodniej muzyce, te kwestie są ledwo dostrzegalne.

Nie słyszałem żadnej muzyki związanej z Occupy. Może coś takiego powstało, a ja po prostu tego nie słyszałem – to nie znaczy, że czegoś takiego nie ma. Z kolei jeśli chodzi o Twoje pytanie, sztuka i muzyka zdecydowanie mogą wpłynąć na politykę, można znaleźć wiele takich przykładów na przestrzeni lat. Wszystko zależy od tego, jak ważny dla zespołu stanie się ten temat i czy będą w stanie wkomponować to w swoją sztukę. Weźmy Crass: ich frontmanem był Steve Ignorant, który miał bardzo dużo do powiedzenia na temat polityki. Już samo to, że lider zespołu wygłaszał nieustanne tyrady, dzielił się swoją wiedzą i swoją historią, było swego rodzaju wypowiedzią artystyczną. Samo w sobie było to środkiem artystycznym, a do tego dochodziło jeszcze jedyne w swoim rodzaju brzmienie zespołu. To doskonały przykład, że sztuka i polityka mogą się ze sobą łączyć. Wydaje mi się, że to, co robimy, nie jest nawet bliskie ich dokonaniom – nasza muzyka jest zdecydowanie bardziej osobista niż polityczna.

Nie jest w tym aspekcie tak bezpośrednia.

To prawda, ale na jakimś poziomie ten przekaz jest wyczuwalny. Na pewno czujemy w tej chwili ciężar tego wszystkiego, po prostu znalazł on takie a nie inne ujście w naszej muzyce.

W przyszłym roku macie zagrać kolejne koncerty. Czy po tej trasie Corrections House będzie dalej istnieć jako zespół i nagracie drugi album? Pytam, bo w przypadku Shrinebuilder wyglądało to trochę inaczej i druga płyty nie było. Czy wszystkim Wam zależy na kontynuacji działalności Corrections House?

Tak. To zupełnie inna relacja niż Shrinebuilder. Każda sytuacja jest inna. Chyba każdy z nas w równym stopniu cieszy się z tego zespołu i z wspólnego grania. Zaczęliśmy już pracę nad kolejną płytą, więc jeśli wszystko pójdzie tak, jak to wygląda w tej chwili, nie powinniśmy mieć żadnego problemu z tworzeniem nowego materiału. Chcemy kontynuować ten projekt, bo jest w nim dużo bardzo skoncentrowanej energii, a każda z zaangażowanych w to osób włożyła wiele pracy w jego powodzenie i wniosła do niego wiele jakościowych treści. To naprawdę robi ogromną różnicę i to widać. To nie chodzi tylko o muzykę, ale o wszystkie inne czynności związane z prowadzeniem zespołu. Jest bardzo wiele czynników, na które nie zwraca się uwagi – na przykład to, że trzeba iść na pocztę i wysłać komuś masę różnego badziewia, regularnie wysyłać maile, dbać o obecność w mediach społecznościowych, organizować sesje fotograficzne, grafikę, teledyski i wszystkie te rzeczy, którymi się zajmujemy. Wszyscy w zespole pracują nad powodzeniem tego projektu i dlatego właśnie to wszystko się dzieje.

English version

Corrections House brings together such musicians as Mike IX Williams (Eyehategod), Scott Kelly (Neurosis), Bruce Lamont (Yakuza), Sanford Parker (Minsk) who brilliantly combine industrial, noise and metal with touches of acoustic guitar and saxophone. After the first single which was released in early 2013, in October the band released their first album Last City Zero and tour Europe for the first time. The last concert of the tour took place in Wroclaw, Poland, and before the gig we interviewed Scott Kelly.

The first shows that you played as Corrections House last year comprised of solo acoustic concerts and a finale with all of you playing together. Then this spring you released a 7-inch with two songs accompanied by videos, and in the fall an album which has a very distinctive sound. How has Corrections House actually evolved into a band with song forms and sound which characterize the album?

That was very natural I guess. We've kept playing these concerts and kind of started creating certain things to be in the set, creating them to be there. With these songs we wanted to kind of define some of the parts we were doing more. Then we just went to the studio and started doing stuff. About half way of that tour we were in the studio and got a bunch of stuff done.

All of you play in different bands with a very distinguished sound. Did you have any idea that this band’s sound would be intentionally visibly different from the other bands you are a part of?

No, it was really just a natural occurrence that happened when we all started playing together. That's all it was. We didn't even intend to have a band. The first time we started talking about it was a year ago and it only happened because we were booking a tour where Bruce and Mike and me were doing our solo materials. It just happened when we started talking about doing a collaboration at the end of the show and then Stanford got involved and the next thing we knew is that we've got a band. There was no preconception of it whatsoever, and the sound just grew from basically what we wanted the live show to sound like.

To what extent was the decision to set up this project based on musical grounds, and to what extent was it related to philosophical kinship, common views on the world?

It just kind of happens that we share views, but it was definitely a musical project. We're kind of drawn to each other and playing within the same scene partly because we share the same sort of view musically and of the world.

Can you say something about the book “Cancer as a Social Activity” by Mike IX Williams, which forms a reference point for the lyrics? I don't think that many people in Poland are familiar with it.

I can't say that much about it because it's Mike's book, Mike wrote and published it. Mike, when did you publish your book?

Mike: 2003.

It's a collection of writings and poems, reflections. It's a great book, you just have to order it from him directly.

I think I even saw it on Amazon.

For a lot of money though.

Did you use the poems from the book like 1:1, or did you rewrite them so they fit into songs, or was it rather about relating to the book topically?

It was more like where they fit, they fit.

Mike: There were also new lyrics written in the studio.

The visual side of the project is quite forceful, sometimes even a bit disturbing. How much effort do you yourselves put into that?

The videos were done by a guy named Brian Sowell, he came up with the initial visions of some stuff, although we gave him some ideas as well, so it's a collaboration, but he executes it, we make suggestions. The other presentations of the band, the symbol, the banners, the photos, all that stuff is our idea.

These videos and promo photos have this kind of “police state”, oppressive atmosphere, sometimes they remind me of the photos from Guantanamo or military prisons in Iraq. Is it something that you were trying to relate to?

Absolutely, that's our reality right now. That was definitely what we're trying to do, and trying to convey with the presentation, the look of the band, the photographs and a general kind of claustrophobic, paranoid feeling of the music. It is all a reflection of the present reality in what we're living right now, where we all are being watched, carefully under control – it just seem like needed to be done.

Also, you are wearing these uniforms at concerts and Seward Fairbury is your “minister of propaganda”, which gives the band a military feel. In the past, bands who made such references were sometimes accused of right-wing attitudes and things like that. They were misunderstood by people or the media. It even happened with The Clash, when some people were offended by “White Riot”, which was actually an anti-racist song, but they saw the title and treated it literally. Has anything like that also occurred to you?

We haven’t heard about anything like that yet. If it inspires people to start a conversation, it's probably a good thing, but I think that the people who know our history, know who we are, and know what side we stand on, hopefully would understand that it's a caricature of a uniform, that we're not starting a political party or anything like that. But it's meant to contribute to the environment, and when we're performing, people will hopefully recognize that on some level.

The discussion if art should be politically related, if it has a potential to trigger social or political change, is centuries old, but western music seems in a retreat in this regard nowadays. There were protest singers across the world through the 20th century, many punk and hardcore bands were politically related. Now we have the Occupy movement, we are in the aftermath of the financial crisis, there is social unrest in several countries, but when you look how much political topics are included in western music, you can barely notice these issues.

I haven't really heard any music related to Occupy. Maybe there is something there and I haven't heard it, but that doesn't mean it's not there. But as far as that question goes, art and music can definitely influence politics, there's plenty of examples of that over many years. It's just a matter of how important that becomes in the band and if they can make that a part of the art. Crass for instance had Steve Ignorant fronting, who had a lot to say politically, actually it became artistic statement itself to have this ranting guy upfront, who was bringing all of his knowledge and his history. Even in itself it's a statement of the artistic expression, and then you mix it with an unique sounding band. They are a perfect example of why it is definitely a fact that art and politics can be tied together. I think that what we're doing it's not quite even close to it, it's much more personal than it is political.

It's not that direct.

It's not, but there's a touch of it, for sure, it's there on some level. We're definitely feeling the weight of it all right now, and it's just how it came out.

You have more shows scheduled for the next year, including Roadburn. Do you think that you will keep Corrections House going after that and record the second album? I’m asking cause for example it didn't really happen with Shrinebuilder. Do all of you have this commitment to continue with Corrections House?

Yeah, we do. It's a very different relationship than Shrinebuilder. Every situation is different. I think we're actually all really equally excited about this band, about doing it. We're already starting to work on another record, so if everything goes the way we feel like it is right now, there should be more and should keep coming. Our plan is to keep going with it, because it has a lot of really focused energy and everybody involved has put a lot of work to make it happen and has brought a lot of quality work to the project. That has made a huge difference, it shows. It's not just music, it's everything else that you have to do to have a band, there's so many elements of running a band that you don't really look at, such a going to the mail box to mail a bunch of shit to somebody, or sending out e-mails regularly, or posting on social media, organizing the photo-shoots and artwork and videos and all the stuff that we were doing. Everybody in this band is working to make shit happen and that's why it is happening.

[Piotr Lewandowski]

subskrybuj newsletter

subskrybuj newsletter